Understanding Pressure Injuries: The 4 Stages

Here are the four stages of a pressure injury, from onset to severe injury.

Pressure injuries—also known as bedsores, pressure sores and decubitus ulcers—are a significant issue in healthcare settings. In the United States alone, 2.5 million people develop pressure sores annually, with 60,000 of those cases being fatal.

Treating pressure sores after they develop can become labor-intensive and quite costly for health institutions, while also causing undue suffering for patients. By placing a larger emphasis on injury prevention from the outset of a hospital stay, we can reduce the incidence of pressure sores and ultimately divert valuable medical personnel to more urgent priorities.

And of course, paying close attention to pressure injury development also serves to elevate patient care and outcomes. The key here is ensuring that every member of your healthcare team is properly trained on prevention, and that begins with recognizing pressure sores for what they are—dangerous, yet preventable, injuries.

What is a pressure injury?

A pressure injury is a skin injury resulting from prolong pressure to the skin. These injuries range in severity, from early-stage pressure sores that simply result in reddened skin to late-stage sores that progress to open wounds, exposing muscle and bone. Pressure injuries can quickly progress from one stage to the next, making early recognition and treatment essential.

The early signs of a pressure sore

Pressure injuries develop for many reasons, so hospitals should have strategies in place to screen for risks among all of their patients. However, there are certain environments that lend themselves to pressure injury development, including moisture, shear, advanced age, limited mobility and lack of access to monitoring technology. It’s important to be vigilant with proactive screening for bedsore development, especially with high-risk patients.

Early warning signs of a pressure injury include:

- Discoloration or dark skin (redder, bluer or more purple than usual)

- An area of skin feeling warmer to the touch than surrounding skin

- Skin that feels firmer in one spot than usual

- Itchy, painful skin

- When the skin is pressed down on, it doesn’t appear lighter

- Swelling on the skin

When monitoring for early signs, it’s helpful to know which areas of a patient’s body are most at risk of developing an injury. According to the Mayo Clinic, for patients spending a long time in bed, monitor the patient’s shoulder blades, hips, lower back, tailbone, back and sides of the head, heels, ankles and skin behind the knees.

For those in a wheelchair, pressure injuries can often develop on the tailbone, spine, shoulder blades, buttocks or contact points between the wheelchair and the arms and legs. It’s also advisable to examine the areas behind tendons and joints.

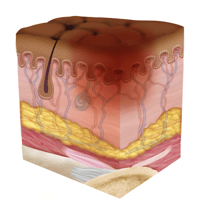

Stage One Pressure Injury: Non-Blanchable Erythema of Intact Skin

Stage One Pressure Injury: Non-Blanchable Erythema of Intact Skin

Early on in pressure ulcer development, the skin is developing injury. While no open sores or broken skin are present yet, the skin may appear redder, warmer or firmer than usual. Known as a non-blanchable erythema of intact skin, the color change may indicate the beginnings of a serious injury to the deep tissue.

Signs of a stage one pressure injury:

- Discolored skin: redder or bluer than typical (may appear purple in darker-skinned patients)

- Skin feels warmer to the touch

- Skin feels firmer or softer in one spot than usual

- Itchy and painful skin

- Skin doesn't blanch (turn white) when pressed

- Swelling or signs of a blood-filled blister

Stage one pressure ulcers present in several ways, far before the skin breaks. Sometimes, they show up as a blood-filled blister, while other times manifest as an area of skin that doesn’t turn white when pressed upon. The lack of visible skin damage isn’t necessarily a cause for relief— stage one pressure ulcers can still cause tissue injury.

How to treat a stage one pressure injury

Once a stage one injury is diagnosed, immediate actions can prevent progression to an open wound requiring urgent care. Treatment requires reducing pressure on the affected area by repositioning the patient and/or using specialized mattress toppers or materials.

Most importantly, stage one pressure injuries require immediate response, as they can quickly progress to stage two and become increasingly difficult to treat. Since stage one injuries do cause tissue damage, healthcare professionals must implement treatment plans for quick healing.

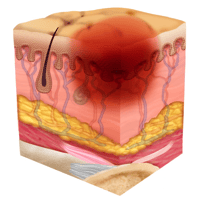

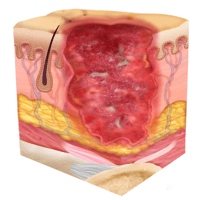

Stage Two Pressure Injury: Partial-Thickness Skin Loss with Exposed Dermis

Stage Two Pressure Injury: Partial-Thickness Skin Loss with Exposed Dermis

In a stage two ulcer, a break in the skin occurs, often including an open sore. Stage two can be very painful, creating serious damage to the skin. Known as partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis, these bed wounds can quickly become something worse and may present as a blood-filled blister.

Signs of a stage two pressure injury:

- Itchy, painful skin that may feel warmer to the touch

- Sore oozing clear liquid, pus, or blood

- Open wound development

- Skin showing signs of erosion or blistering, but not yet covered by slough

When identifying a stage two ulcer, it can be helpful to differentiate it from stage one. During stage one, tissue injury is just beginning, but is not yet visible. However, when a sore develops to stage two, the skin will open, forming a visible ulcer. Health care professionals and patients may see a small abrasion, a blood-filled blister or a dip in the skin. Tissue damage may become apparent, causing serious issues if not dealt with quickly.

How to treat a stage two pressure injury

By treating a stage two pressure injury with urgency, you may be able to avoid deeper tissue damage or infection. It’s vital to implement wound care strategies right away, taking steps such as removing pressure from the affected areas of the skin, turning the patient regularly and integrating technology that helps mointor the skin.

Because stage two pressure injuries can advance to stage three quickly, immediate action by health care staff is required to prevent further tissue damage and infection.

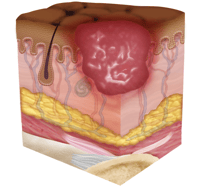

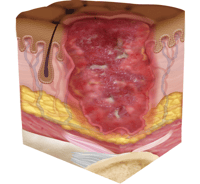

Stage Three Pressure Injury: Full-Thickness Skin Loss

Stage Three Pressure Injury: Full-Thickness Skin Loss

In stage three, the pressure injury has developed into the soft tissue underneath the skin. Known as full-thickness skin loss, this stage may show a deep wound, especially in an area with more adipose tissue.

Stage three injuries may begin extending down into the tissue, showing exposed fat. At this stage, the injury may not even cause pain to the patient, indicating possible deep tissue damage.

Signs of a stage three pressure injury:

- Skin has developed a crater, potentially with visible adipose tissue

- Sore has a foul odor

- Sore is oozing clear liquid, pus, or blood

- Sore may be covered by slough, but not in a way that obscures tissue visibility

When identifying a stage three pressure injury, you'll notice a significant progression from earlier stages. Unlike stage two, where damage is limited to the upper layers of skin, stage three injuries extend deeper into the subcutaneous tissue. These injuries create crater-like wounds where adipose (fat) tissue is often visible. The wound edges may be well-defined, and the surrounding skin might show signs of damage from pressure and reduced blood flow. At this stage, the depth of tissue damage becomes much more concerning, and the risk of infection increases substantially.

How to treat a stage three pressure injury

Wound care strategies must be implemented immediately, particularly if any signs of infection are present. The goal is to prevent progression to stage four. Staff should implement repositioning and pressure-relieving strategies to reduce pressure on the wound, while being careful not to create conditions for new pressure injuries to develop.

Every healthcare institution has wound care protocols that should be followed with urgency. Irrigate and properly dress the wound, and prescribe antibiotics if required.

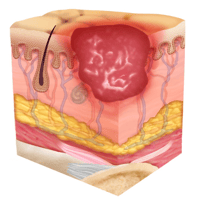

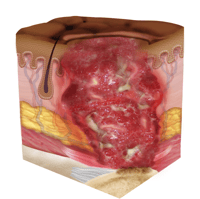

Stage Four Pressure Injury: Full-Thickness Skin and Tissue Loss

Stage Four Pressure Injury: Full-Thickness Skin and Tissue Loss

By the final and most serious stage of a pressure sore, the skin may have receded into the muscle and bone, causing lasting damage to the skin and underlying areas. Known as full-thickness skin and tissue loss, this stage can involve visible or palpable fascia, tendon, muscle and bone, and even dead tissue.

In a stage four pressure injury, you’ll see a marked difference from earlier stages. Stage four injuries are incredibly serious, and may show visible deep tissue damage, drainage, pus and a wound covered with a thin layer of eschar. These often become infected and may require surgery to repair.

Signs of a stage four pressure injury:

- Skin has developed a crater, with wound bed possibly including visible adipose tissue, muscle, or bone

- Sore has a foul odor

- Sore is oozing clear liquid, pus, or blood, or showing other signs of infection

- Skin may have turned black with dead tissue

- Large, deep, and noticeable sore, possibly covered by slough or eschar

These injuries are starkly different from earlier stages, with extensive destruction reaching into muscle tissue and potentially exposing tendons and bone. The extensive depth creates substantial risk for serious complications, including osteomyelitis, sepsis, and can be life-threatening. The development of a stage four pressure injury typically indicates prolonged tissue compression and inadequate intervention at earlier stages. Management requires intensive multidisciplinary care, including specialized wound techniques, nutritional support, infection control, and potentially surgical intervention, as these wounds heal slowly and may result in permanent tissue loss.

How to treat a stage four pressure injury

Stage four pressure injuries require immediate wound care strategies and may necessitate both surgery and serious antibiotics. These bedsores are dangerous and should be treated accordingly.

Ideally, prevention would have begun at the start of the hospital stay with risk assessment technology. By using this technology proactively, healthcare professionals can mitigate the development.

Healthcare institutions should follow their wound care protocols immediately, including irrigating and properly dressing the wound, and administering antibiotics if needed. Stage four pressure injuries may require surgery, and consultation with a pressure ulcer advisory panel may be necessary.

Equipment to prevent pressure injuries

Integrating sensing technology into your institution’s pressure injury treatment and prevention strategies can significantly improve both patient outcomes and hospital operations, reducing staff workloads and increasing efficiency.

XSENSOR offers technology for dynamic sensing and continuous pressure monitoring, giving medical professionals accurate, real-time data to inform individualized treatment—and, ideally, the complete prevention—of pressure injuries.

XSENSOR’s ForeSite technology is specifically designed to help clinicians alleviate and prevent the formation and progression of pressure sores, helping you address three main culprits: surgical tables, hospital beds and wheelchairs.

- For hospital beds: Our unique ForeSite Intelligent Surface mattress system uses more than 1500 sensor cells on the surface of a mattress or fitted cover to measure patient body surface pressures, displaying data in real time for continuous monitoring. The system includes a turn clock to track repositioning and informs better patient care.

- For surgical tables: Our ForeSite OR system carries the same technology through to the operating room, which is excellent for managing risk in longer surgeries.

- For wheelchairs: Our ForeSite SS system utilizes advanced sensing for seating assessment of those in wheelchairs.

At XSENSOR, we support health professionals in providing high-quality patient care through intelligent dynamic sensing technology. Contact us today, and we’ll elevate your standard of care together.

Report typo or error by contacting XSENSOR